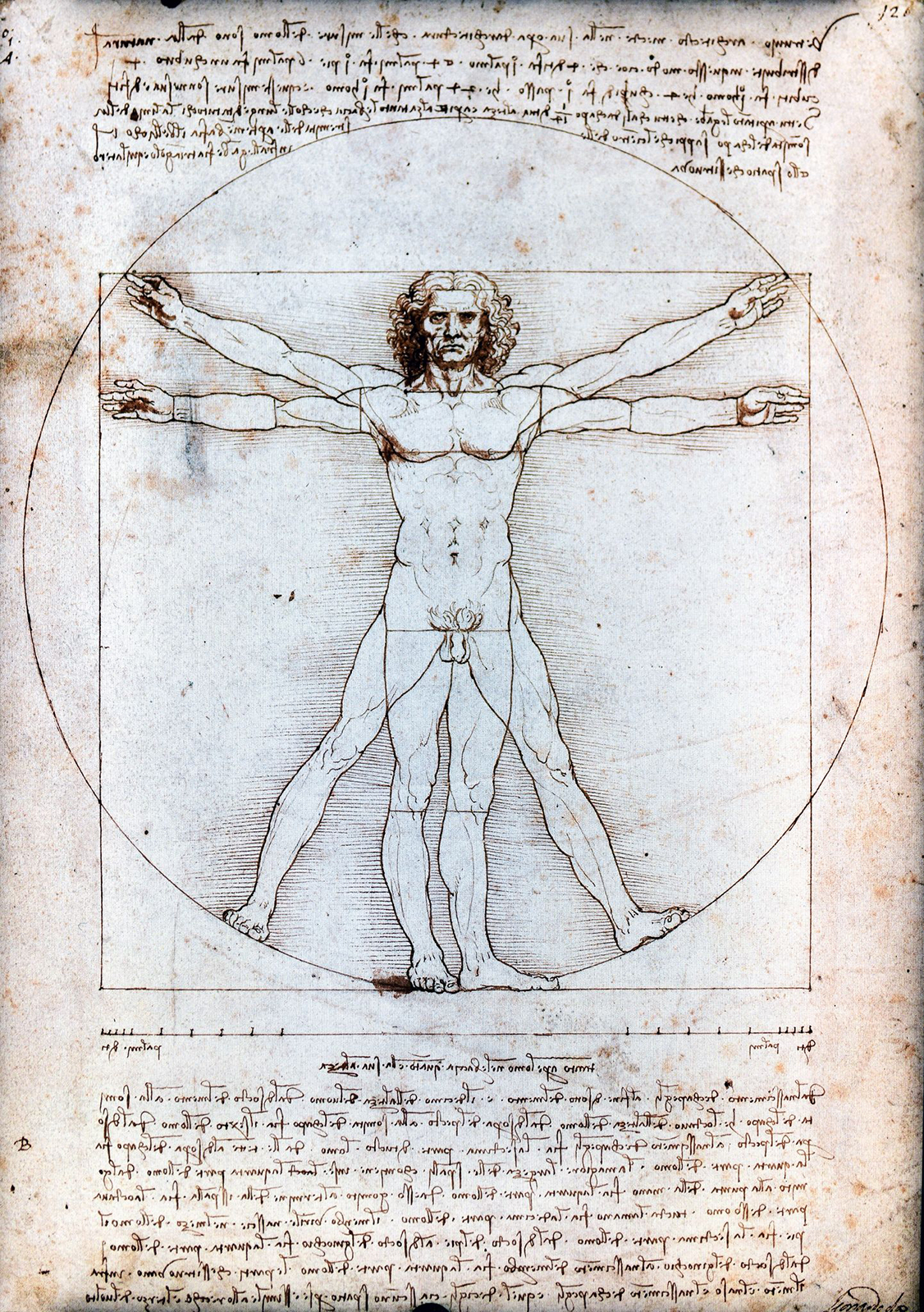

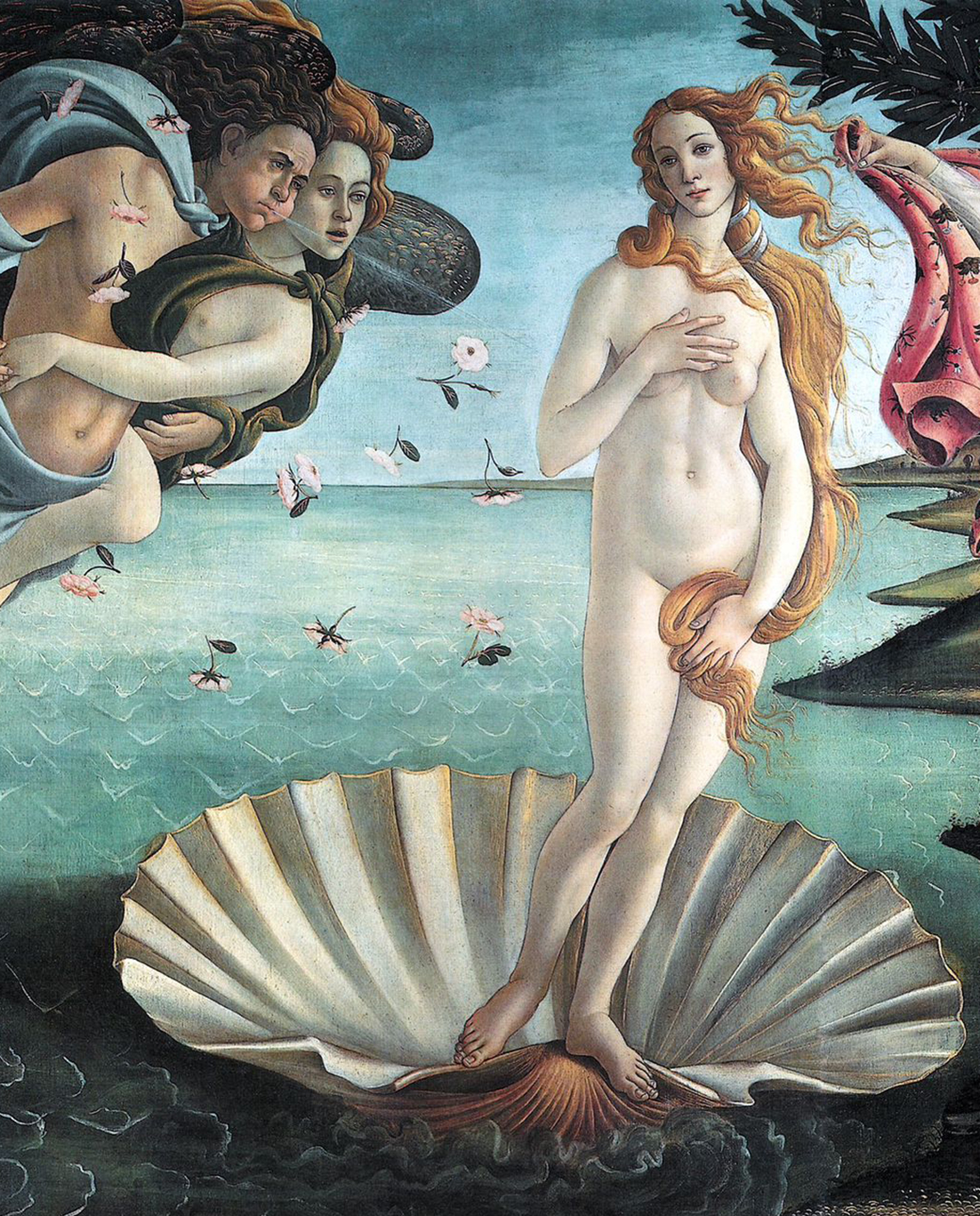

Central Symmetry and Its Symbolism in European Art Central symmetry—where elements radiate from or mirror a central point—has shaped European art for millennia, embodying ideals of harmony, divinity, and human intellect. Ancient Roots In ancient Greece, symmetry symbolized cosmic order. The Parthenon’s proportions and vase paintings used radial balance to reflect ideal beauty and the gods’ perfection. Roman mosaics later adopted these principles, linking symmetry to imperial power. Medieval Sacred Geometry Christian art embraced central symmetry as a divine language. Rose windows in Gothic cathedrals (e.g., Notre-Dame) used radial symmetry to depict heaven’s light and the universe’s order. Illuminated manuscripts, like the Book of Kells, employed intricate symmetric patterns to honor sacred texts. Renaissance: Humanism and Perspective Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man fused art and science, using central symmetry to illustrate human proportions as a microcosm of the universe. Renaissance painters, such as Botticelli in The Birth of Venus, centered figures to evoke balance and classical ideals. Baroque Dynamism While the Baroque era favored asymmetry, artists like Caravaggio and Bernini used subtle central symmetry in compositions (e.g., The Ecstasy of Saint Teresa) to draw viewers’ eyes to spiritual or emotional focal points, creating dramatic tension. Symbolism and the Occult The 19th-century Symbolist movement revived esoteric traditions. Odilon Redon’s symmetric, dreamlike works explored the subconscious, while theosophical artists used mandala-like forms to represent unity and transcendence. Modern Abstraction Piet Mondrian’s grids and Wassily Kandinsky’s concentric circles abstracted symmetry into pure form, reflecting the search for universal truths. The Bauhaus movement later codified symmetry as a tool for functional, democratic design. Religious and Political Symbolism Central symmetry in European heraldry (coats of arms, flags) signified authority and stability. Soviet constructivists, like El Lissitzky, used geometric symmetry to promote revolutionary ideals, blending art and propaganda. Contemporary Reflections Today, artists like Anish Kapoor (Cloud Gate) use symmetry to explore perception and infinity. Digital art and architecture continue to reinterpret central symmetry, questioning its role in a fragmented, postmodern world. Legacy From sacred spaces to secular masterpieces, central symmetry in European art reveals a persistent quest for meaning—whether divine, scientific, or deeply human. It remains a visual language of balance, inviting viewers to seek harmony in chaos.   Philosophical Underpinnings of Renaissance Symmetry The Renaissance fascination with central symmetry was not merely aesthetic—it was deeply rooted in the era’s intellectual and philosophical revolutions. Here’s how symmetry became a visual manifestation of Renaissance thought: 1. Neo-Platonism: The Divine Blueprint Renaissance philosophers, inspired by Marsilio Ficino and Pico della Mirandola, revived Neo-Platonic ideas that saw the universe as a harmonious, geometrically ordered cosmos. Symmetry was the visible expression of the « divine mind »— a reflection of God’s perfect design. The circle, the most symmetrical shape, symbolized eternity, unity, and the infinite, while the square represented the material world. Artists like Botticelli and Leonardo used these forms to evoke the connection between the earthly and the divine, as seen in works like The Birth of Venus and Vitruvian Man. 2. Humanism: Man as the Measure Humanist thinkers, such as Leon Battista Alberti, argued that beauty arose from proportion and order, which mirrored the rational structure of the universe. Symmetry in art and architecture became a celebration of human potential, positioning mankind as both the creator and the measure of harmony. This idea was central to Alberti’s De re aedificatoria (On the Art of Building), where he described symmetry as the « soul of architecture » — a principle that elevated human creations to the level of divine perfection. 3. The Hermetic Tradition: As Above, So Below The Corpus Hermeticum, rediscovered in the 15th century, taught that the macrocosm (universe) and microcosm (human) were linked through geometric harmony. Symmetry in Renaissance art—such as the concentric circles in Francesco di Giorgio Martini’s architectural drawings—embodied this principle, suggesting that understanding proportion could unlock the secrets of both the heavens and the human soul. 4. The Golden Ratio: A Bridge Between Math and Mysticism The golden ratio (phi), explored by Luca Pacioli in De divina proportione (1509), was seen as a divine proportion that governed all creation. Pacioli, a collaborator of Leonardo da Vinci, believed that symmetry and proportion were not just mathematical concepts but moral and spiritual ideals. The use of the golden ratio in art, from the Mona Lisa to the Last Supper, reflected the Renaissance belief that beauty, truth, and goodness were interconnected. 5. The Occult and Alchemy: Symmetry as Sacred Knowledge Symmetry also held esoteric significance. Alchemists and mystics, like Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, saw geometric patterns as keys to hidden knowledge. Symmetrical diagrams, such as those in Robert Fludd’s writings, represented the balance of opposites—sulfur and mercury, sun and moon—essential for spiritual transformation. This idea influenced artists to use symmetry as a tool for conveying deeper, often hidden, meanings. 6. The Union of Faith and Reason The Renaissance sought to reconcile Christian theology with classical philosophy. Symmetry in religious art—such as the radial designs of rose windows or the balanced compositions of Raphael’s Madonnas — symbolized the harmony between faith and reason. The central point in these works often represented God as the source of all order, while the surrounding symmetry reflected the logical structure of creation. 7. The Artist as Philosopher-Scientist Figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer embodied the Renaissance ideal of the artist as a philosopher-scientist. Their studies of anatomy, perspective, and geometry were not just technical exercises but quests for universal truth. Dürer’s Four Books on Human Proportion (1528) argued that symmetry in the human body revealed the divine plan, blending empirical observation with metaphysical speculation. 8. Symmetry and the New Worldview The Renaissance symmetry was more than a stylistic choice — it was a worldview. By organizing space and form according to mathematical principles, artists and architects expressed a belief in a rational, orderly universe, one that could be understood and even mastered through human ingenuity. This philosophy laid the groundwork for the Scientific Revolution, where the same principles of symmetry and proportion would be applied to the laws of nature. |

Central Symmetry in Renaissance Art: An Exploration The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) marked a rebirth of classical ideals, where central symmetry became a powerful tool to express humanism, divine order, and scientific inquiry. Here’s how symmetry shaped this transformative era: 1. Revival of Classical Harmony Renaissance artists rediscovered ancient Greek and Roman principles, using central symmetry to evoke the "perfect proportions" of antiquity. Buildings like Brunelleschi’s Pazzi Chapel mirrored the symmetry of Roman temples, symbolizing rationality and cosmic order. 2. Humanism and the Vitruvian Ideal Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) epitomized the era’s fusion of art and science. The symmetrical figure inscribed in a circle and square represented humanity as the measure of all things—a microcosm of the universe, balancing math, anatomy, and philosophy. 3. Sacred Geometry in Religious Art Symmetry in religious works, such as Raphael’s The School of Athens (1509–1511), reflected divine harmony. The central vanishing point, framed by arches and figures, directed viewers toward Plato and Aristotle, symbolizing the unity of faith and reason. 4. Architectural Mastery Filippo Brunelleschi’s Dome of Florence Cathedral used radial symmetry to create a celestial effect, while Andrea Palladio’s villas (e.g., Villa Rotonda) employed central plans to harmonize human dwellings with nature, echoing Platonic ideals. 5. Perspective and the Central Point The invention of linear perspective by Brunelleschi allowed artists to create symmetrical, three-dimensional spaces on flat surfaces. Piero della Francesca’s Flagellation of Christ (c. 1455–1460) used a central vanishing point to draw viewers into a sacred, mathematically ordered world. 6. Portraits of Power and Virtue Symmetrical compositions in portraits, like Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, conveyed balance and inner harmony. The central positioning of figures emphasized their importance, reflecting the era’s celebration of individualism and virtue. 7. Allegorical Works Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (c. 1484–1486) centered the goddess in a symmetrical shell, surrounded by balanced figures and flowing lines. The symmetry underscored Venus as a symbol of love and beauty, reviving classical mythology with Christian undertones. 8. The Influence of Neo-Platonism Philosophers like Marsilio Ficino linked symmetry to the "divine proportion" (golden ratio). Artists such as Michelangelo incorporated these ideas into works like the Creation of Adam (Sistine Chapel), where God and Adam’s outstretched fingers form a symmetrical axis, symbolizing the spark of life. 9. Symmetry in Print and Decorative Arts Albrecht Dürer’s engravings, like Melencolia I (1514), used geometric symmetry to explore melancholy and creativity. The magic square and compass in the image reflected the Renaissance quest to unite art, science, and the occult. 10. Legacy: Bridging Art and Science The Renaissance obsession with symmetry laid the groundwork for modern mathematics and physics. By treating art as a science and science as an art, figures like Leonardo and Dürer transformed symmetry from a stylistic choice into a philosophy—a bridge between the visible and invisible worlds.   Symmetry, Geometry, and Perspective in Renaissance Art and Science The Renaissance (14th–17th centuries) witnessed a revolutionary fusion of symmetry, geometry, and perspective, transforming both art and science into tools for understanding the universe, humanity, and the divine. Here’s how these principles reshaped the era: 1. The Revival of Classical Geometry Renaissance thinkers rediscovered Euclidean geometry through ancient texts, seeing it as the foundation of order and beauty. Artists like Paolo Uccello and Piero della Francesca studied Platonic solids and proportional systems, believing geometry revealed the hidden structure of reality. 2. Linear Perspective: The Science of Illusion Filippo Brunelleschi’s invention of linear perspective (c. 1415) used geometry to create the illusion of depth on a flat surface. By centering compositions on a vanishing point, artists like Masaccio (Trinity, 1425) made sacred scenes feel tangible, bridging the gap between heaven and earth. 3. Symmetry as Divine Harmony Inspired by Neo-Platonism, Renaissance artists used central symmetry to reflect the perfect order of the cosmos. Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man (1490) embodied this ideal, merging human anatomy with geometric perfection to symbolize the unity of man and universe. 4. Sacred Geometry in Architecture Architects like Brunelleschi and Palladio designed churches and villas using geometric proportions, such as the golden ratio (phi). The Dome of Florence Cathedral and Villa Rotonda became physical manifestations of harmony, blending math, aesthetics, and spirituality. 5. The Golden Ratio: A Universal Principle Luca Pacioli’s De divina proportione (1509), illustrated by Leonardo, celebrated the golden ratio as a divine secret governing nature and art. From the Mona Lisa’s composition to the Last Supper’s perspective, this ratio became a tool for creating visually and spiritually balanced works. 6. Anatomy and Proportion Artists dissected corpses to master human proportions, applying geometric grids to achieve lifelike symmetry. Dürer’s Four Books on Human Proportion (1528) codified these rules, arguing that beauty arose from mathematical precision. 7. Perspective as a Metaphor for Knowledge Perspective wasn’t just a technique—it symbolized the Renaissance worldview. The vanishing point represented God’s infinite nature, while the converging lines mirrored the human quest for understanding. Raphael’s School of Athens (1511) used perspective to depict philosophy as a path to truth. 8. Geometry in Science and Cosmology Scientists like Copernicus and Kepler applied geometric principles to astronomy. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion (1609) revealed the symmetry of the solar system, echoing the Renaissance belief that the universe was a harmonious, divinely ordered machine. 9. The Artist-Scientist Ideal Figures like Leonardo da Vinci embodied the union of art and science. His studies of optics, anatomy, and engineering were grounded in geometry, proving that symmetry and perspective were keys to unlocking nature’s secrets. 10. Legacy: A New Way of Seeing The Renaissance fusion of geometry, symmetry, and perspective didn’t just revolutionize art—it laid the foundation for modern science, mathematics, and even digital design. By treating the canvas as a window into reality. Renaissance masters taught us to see the world through the lens of order, reason, and beauty.   Leonardo’s Geometric Legacy: Shaping Art and Science After the Renaissance Leonardo da Vinci’s geometric principles didn’t just define his era—they revolutionized art and science for centuries, bridging the Renaissance to modernity. His ideas became a foundation for innovation, inspiring artists to see beauty in mathematics and scientists to seek order in nature. Here’s how his legacy unfolded: 1. Art: From Mannerism to the Baroque Mannerism (16th century): Artists like Parmigianino and Pontormo twisted Leonardo’s geometric ideals into elongated, asymmetrical forms, but his influence persisted in their use of dynamic perspective and anatomical precision. Parmigianino’s Madonna with the Long Neck (1534) plays with proportion, yet its underlying structure reflects Leonardo’s studies of idealized geometry. Baroque (17th century): While the Baroque embraced drama and movement, masters like Caravaggio and Bernini used Leonardo’s chiaroscuro and pyramidal compositions to create depth. Caravaggio’s The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600) employs a diagonal beam of light — a geometric device Leonardo pioneered—to guide the viewer’s eye and evoke divine intervention. Neoclassicism (18th–19th centuries): Artists like Jacques-Louis David returned to Leonardo’s classical symmetry and perspective, rejecting Baroque excess. David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784) uses a grid-like composition and central vanishing point, echoing Leonardo’s Last Supper to convey moral clarity and rational order. 2. Science: From Anatomy to Astronomy Anatomy and Medicine: Leonardo’s geometric dissections influenced Andreas Vesalius, whose *De humani corporis fabrica* (1543) became the cornerstone of modern anatomy. Vesalius’s illustrations, like Leonardo’s, used proportional grids to depict the body’s systems, proving that art and science were inseparable in understanding human life. Optics and Physics: Leonardo’s studies of light, shadow, and reflection inspired Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton. Kepler’s work on optical lenses (1611) built on Leonardo’s observations of how light interacts with geometric forms, while Newton’s Opticks* (1704) explored similar principles of refraction and color. Astronomy and Cosmology: Leonardo’s belief in a geometrically ordered universe foreshadowed Galileo’s and Kepler’s discoveries. Kepler’s laws of planetary motion (1609–1619) revealed the symmetry of orbits, while Galileo’s telescopic observations confirmed that nature followed mathematical laws — a direct descendant of Leonardo’s worldview. Engineering and Invention: Leonardo’s geometric sketches of flying machines, bridges, and hydraulic systems became blueprints for later inventors. The Wright brothers studied his ornithopter designs, and modern aerodynamics owes much to his early insights into symmetry and airflow. His ideal city plans, with radial streets and symmetrical layouts, influenced urban design from the 18th century onward. 3. The Birth of Modern Science The Scientific Revolution: Leonardo’s empirical approach — observing nature, testing hypotheses, and using geometry to explain phenomena—became the methodological foundation of the Scientific Revolution. Figures like Francis Bacon and René Descartes adopted his interdisciplinary mindset, arguing that mathematics was the language of science. Cartography and Geography: Leonardo’s geometric maps and studies of water flow influenced Gerardus Mercator, whose 1569 world map used projection techniques rooted in Renaissance perspective. Modern GIS (Geographic Information Systems) still rely on these principles to represent the Earth’s curvature. 4. The Digital Age: Leonardo’s Algorithms Computer Graphics and 3D Modeling: Leonardo’s perspective grids and anatomical studies are the ancestors of CGI and 3D animation. Pixar’s artists and engineers cite his work as inspiration for rendering light, shadow, and human movement in films like Toy Story and The Incredibles. Artificial Intelligence and Robotics: Leonardo’s mechanical knight and automata designs foreshadowed modern robotics. His belief that geometry governed motion is now applied in AI algorithms for machine learning and biomechanics, where symmetry and proportion are key to designing humanoid robots. Fractals and Chaos Theory: Leonardo’s observations of **natural patterns — like the spirals in water and hair — prefigured fractal geometry. Scientists like Benoît Mandelbrot later formalized these ideas, revealing that Leonardo’s intuitive understanding of recursion was centuries ahead of its time. 5. A Timeless Philosophy Leonardo’s greatest gift was his holistic vision: the idea that art, science, and nature are governed by the same geometric principles. This philosophy shaped the Enlightenment’s faith in reason, Romanticism’s awe of nature, and modernism’s break with tradition — all while his mathematical approach to beauty remains a touchstone for creators today.   Leonardo’s Geometric Legacy in AI and Architecture AI: Learning from Leonardo’s Algorithms of Nature 1. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning Leonardo’s studies of natural patterns —water eddies, leaf arrangements, muscle fibers—prefigured modern pattern recognition. AI algorithms now use similar geometric and fractal analysis to interpret medical images, satellite data, and even handwriting. 2. Computer Vision and Perspective His linear perspective techniques inspired 3D modeling and computer vision. AI systems, like those in self-driving cars, rely on vanishing point detection and depth estimation — direct descendants of Leonardo’s methods for rendering space on a flat surface. 3. Biomechanics and Robotics Leonardo’s anatomical sketches of human movement informed biomechanical AI. Today, robots and prosthetics use geometric motion capture to mimic human gait and gestures, applying his principles of proportion and symmetry to mechanical design. 4. Generative Art and Neural Networks AI art tools, such as DALL·E and MidJourney, generate images using symmetry and composition rules Leonardo pioneered. His sfumato technique (blending tones) is now replicated in AI algorithms that create hyper-realistic textures and lighting. 5. Fractals and Chaos Theory in AI Leonardo’s observations of recursive patterns in nature (e.g., tree branches, river deltas) align with fractal geometry, a cornerstone of AI models for complex systems — from weather prediction to financial markets. 6. Ethical AI and Human-Centric Design Leonardo’s human-centered approach —studying anatomy, emotions, and perception—inspires ethical AI design, Modern AI prioritizes user experience and accessibility, mirroring his belief that technology should serve humanity. Architecture: Building with Leonardo’s Blueprints 7. Radial and Symmetrical Urban Planning Leonardo’s ideal city designs (e.g., radial streets, symmetrical layouts) influenced modern urbanism. Cities like Washington, D.C. and Brasília echo his geometric vision, using central symmetry for efficiency and aesthetics. 8. Parametric and Algorithmic Design Contemporary architects use parametric software (e.g., Grasshopper, Rhino) to create organic, geometrically complex structures — a digital evolution of Leonardo’s interlocking forms and proportional studies. 9. Sustainable and Biomimetic Architecture Leonardo’s observations of nature’s efficiency (e.g., bird flight, plant growth) inspired biomimicry in architecture. Buildings like The Eden Project (UK) and Eastgate Centre (Zimbabwe) mimic natural geometries for energy efficiency, just as he envisioned. 10. Structural Engineering and Stability His bridge and dome designs, grounded in geometric stability, inform modern tensile structures and earthquake-resistant buildings. The Salginatobel Bridge (Switzerland) and Sydney Opera House reflect his principles of load distribution and elegant symmetry. 11. Light and Spatial Illusion Leonardo’s mastery of chiaroscuro (light/shadow contrast) is now applied in architectural lighting design. Museums, theaters, and sacred spaces use dynamic lighting to create depth and emotion, much like his paintings. 12. Modular and Prefabricated Construction His interlocking geometric modules (e.g., fortress designs) foreshadowed modular architecture. Today, prefab homes and disaster-relief shelters use symmetrical, repeatable units for rapid assembly—a practical extension of his innovative spirit. 13. Digital Fabrication and 3D Printing Leonardo’s precise geometric sketches are now brought to life via 3D printing. Architects like Neri Oxman (MIT) create biologically inspired structures using his principles of form follows function. 14. Sacred Geometry in Modern Spaces From Le Corbusier’s Modulor to Zaha Hadid’s fluid geometries, Leonardo’s sacred proportions (golden ratio, Fibonacci sequences) continue to shape iconic buildings, blending math, art, and spirituality. 15. The Fusion of Art and Engineering Leonardo’s artist-engineer identity lives on in firms like Foster + Partners and BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group), where aesthetic symmetry and structural innovation coexist—proving his belief that beauty and utility are one. Final Thought: Leonardo’s genius lies in his ability to see the unseen — turning geometry into a language for both machines and monuments, Today, AI and architecture are simply new canvases for his timeless principles. |